Visiting Dr. Payne

The finale of my trip to Ithaca, the plump maraschino atop the sundae, was a breakfast invitation by bioacoustician and writer Katy Payne. In the 1970's, Katy and her husband Roger blew the world of cetacean biology wide open with their work on the songs of humpback whales. They were the first to record, study, and try to decipher the astounding underwater songs of what whalers used to call "sea canaries." What a wonderful name for a multi-ton animal.

More recently, Dr. Payne has worked with elephants in Africa. It started simply enough, with a visit to an elephant house at a zoo. She felt, rather than heard, a rumble in her breastbone, the same kind of thrumming you get when you feel, rather than hear, a ruffed grouse. It was more like a thrill than a sound. She turned to her friends and said, "There's something going on in here." That moment of enlightenment led her to her discovery that elephants communicate in ultra low-frequency infrasound, and that communication may travel over hundreds of miles. Yes. What are they saying? I'm reading her book, Silent Thunder, and it is setting me afire.

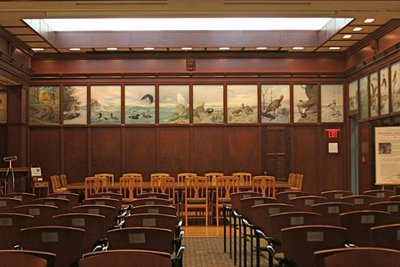

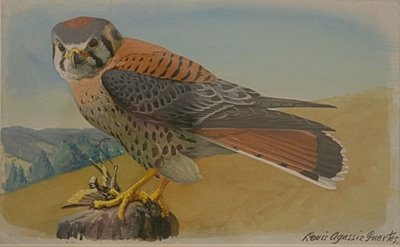

Katy Payne's grandfather was Louis Agassiz Fuertes.

She never knew him, since he died so young, but I have studied pictures of him and I can tell you that he is there in her eyes, in her warmth and kindness, in her sensitivity to animals, her inquisitiveness, her deeply artistic way of thinking, and in her writing. I was almost overwhelmed on meeting her; I had a jolt of recognition that came from somewhere other than mere physical resemblance. I felt as if I were meeting Louis himself.

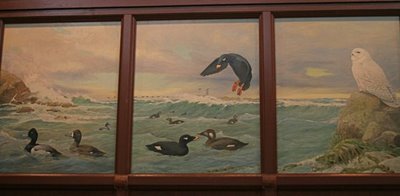

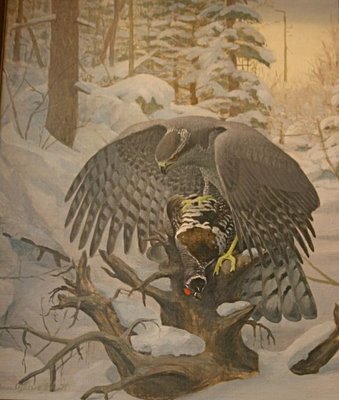

There are some L.A.F. paintings in Katy's homey, naturalist's living room. One is this little crow study.

"Remember," Katy said, "that he had no photographs to work from. He had to figure out the wing positions on his own."

What a gorgeous wing, what a gorgeous little painting, so full of crow lore and winterchill. Look how the shading on the distal half of the crow's raised wing makes it bend out toward you. Ahhhh.

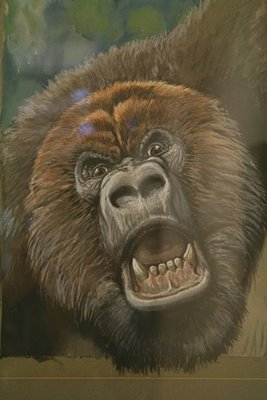

I was utterly arrested by this Fuertes life sketch of a ferret, perhaps a black-footed ferret.

How perfectly he understood how its weight is distributed, how its fur flows and reverses; the sacklike bunching up of the abdominal skin. You can see how it could turn inside that loose skin, as weasels are said to do. And there's something birdlike about the neck and head. It could only have been done from life.

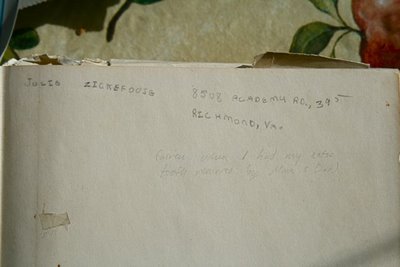

How perfectly he understood how its weight is distributed, how its fur flows and reverses; the sacklike bunching up of the abdominal skin. You can see how it could turn inside that loose skin, as weasels are said to do. And there's something birdlike about the neck and head. It could only have been done from life.As Katy and I talked and looked through photographic scrapbooks of the Merriman Arctic Expedition, of which Louis was a vital part, I felt as if I'd known her all my life. And especially so as she dithered about the soy-milk waffles she made for us, which were quite delicious, but which she felt weren't quite up to snuff. Sounded just like something I'd try, just like the things I'd say. Chet Baker could see he was in for a long haul as we talked, so after casing the entire house and watching squirrels outside for awhile, he jumped up in a comfy chair and pawed up a hand-loomed throw just so, flopping down and curling up with a piglike grunt. "Make yourself at home, Bacon!" I said, and we laughed. Sometimes you meet someone like Katy and you wonder why you haven't been friends forever, but you feel like you ought to get it started already. Even our cowlicks are mirror-image. Pfffft.

photo by Alan Poole. Thank you a million, AP.

photo by Alan Poole. Thank you a million, AP.What a gift to the world is this scientist, this writer. Read Silent Thunder. Louis would be so proud.

Labels: black-footed ferret sketch, elephant communication, Katy Payne, Louis Agassiz Fuertes