Capuchinbird Trek

What an inviting name for a nature trail! The South American bushmaster (Lachesis muta) is one of the world's most dangerous venomous snakes--a big sucker, the biggest known having been 12' long, given to looping its browny length in the top of a shrub and waiting by the trail for something to walk by that's small enough to inject and swallow. I've seen one, in Brazil, and I'll never forget it. Oh, there you are, right there at chest level, looking like a rope thrown over a shrub. Big devil you are. I'm backing away from you now. I have things to do, places to go, people to see.

What an inviting name for a nature trail! The South American bushmaster (Lachesis muta) is one of the world's most dangerous venomous snakes--a big sucker, the biggest known having been 12' long, given to looping its browny length in the top of a shrub and waiting by the trail for something to walk by that's small enough to inject and swallow. I've seen one, in Brazil, and I'll never forget it. Oh, there you are, right there at chest level, looking like a rope thrown over a shrub. Big devil you are. I'm backing away from you now. I have things to do, places to go, people to see.On our last morning at Iwokrama Lodge, we made a short trek to see a lekking site for capuchinbirds. I apologize if that sentence looks like Greek to you; it sort of is. A lek is a place where male birds get together to display, hoping to attract females. Famous North American birds that lek are prairie chickens, sage and sharp-tailed grouse. Woodcocks lek, too, sort of, although they're more dispersed. The idea is that a bunch of noisy male birds gathered together in one place have a greater chance of attracting interested females than one noisy male bird at location X, and another at location Z.

There are lots of birds that lek in the tropics. They include many species of manakins and cotingas, the darlings of tropical birders. Guyana is the most cotinga-rich place I've ever been. Purple-throated fruitcrows, pompadour and purple-breasted cotingas, Guianian red-cotingas, swallow-wings, puffbirds, nunbirds and capuchinbirds--they are the ones that birders dream of and drool over as they plan their trips. They're big, colorful and bizarre, and the capuchinbird (or calfbird, as I know it) is one of the weirdest. It's a large, cinnamon toast-colored bird with a bald gray head (and a monklike hood of brown feathers, hence the name capuchinbird). Its call sounds like a cross between a chainsaw and a calf--a rolling bup-bup-bup-bup-brrr that sounds like a chainsaw just being started, ending in a long, nasal WRAAAAAAHHHHHH that recalls a lonely calf or a spadefoot toad. There's a mechanical quality to it that makes you question whether a bird could make such a sound. It's almost more froglike than birdlike, and very loud. It comes from the very top of the canopy, which in primary rainforest is very high up indeed--80-120 feet. Arggh. Can you feel your neck cramping?

On the way to the lek, we spotted a beautiful passionflower vine

an intriguingly fluted termite nest

an intriguingly fluted termite nest more monkeyladders

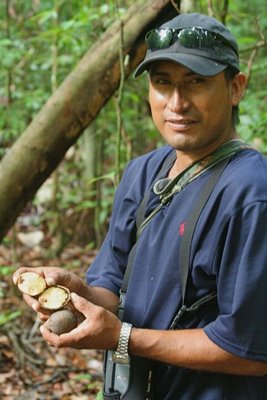

more monkeyladders some bizarre woody seed capsules, each with a perfectly fitted lid, called monkey cups

some bizarre woody seed capsules, each with a perfectly fitted lid, called monkey cups I really, really wanted to bring one home. They were big--about 8" long--and looked useful somehow, I don't know, maybe to carry something in? but that's against the rules, and besides, they were too rotty. Everything on the forest floor in Guyana is pretty rotty. If you could just get it when it first fell.

I really, really wanted to bring one home. They were big--about 8" long--and looked useful somehow, I don't know, maybe to carry something in? but that's against the rules, and besides, they were too rotty. Everything on the forest floor in Guyana is pretty rotty. If you could just get it when it first fell.We found the extraordinary cotyledons of a mystery seedling, a green angel on the forest floor

but no bushmasters. Deep sigh. It would have been fine to see one, as long as we saw it first.

but no bushmasters. Deep sigh. It would have been fine to see one, as long as we saw it first.It wasn't long before we could hear the wraaah of the capuchinbirds sifting through the hot morning mist. We checked the ground for snakes and army ants and sat down, because the birds were too far up in the canopy to bend our necks back far enough to see them any other way. Here's the first thing I was able to pick out:

Bear with me here. See the two little orange balls? I told you they were weird birds. You can see them again in this picture, but they aren't quite as prominent.

Bear with me here. See the two little orange balls? I told you they were weird birds. You can see them again in this picture, but they aren't quite as prominent. They're under the tail of the male capuchinbird, and they aren't what you think--merely undertail covert feathers that can in some bizarre way be (oh, here I go) erec... puffed out... so they look for all the world like...well, you already have the idea.

They're under the tail of the male capuchinbird, and they aren't what you think--merely undertail covert feathers that can in some bizarre way be (oh, here I go) erec... puffed out... so they look for all the world like...well, you already have the idea.Here's the upper body and head of the capuchinbird.

Kind of vulturine, with a big ruff of cinnamon feathers at the back of the skull.

Kind of vulturine, with a big ruff of cinnamon feathers at the back of the skull.I cannot tell you how difficult it was to get an acceptable picture of this bird, shooting straight over our heads and into a bright sunny sky. I had to open the aperture all the way to be able to get anything more than a black blot.

Capuchinbirds eat large-seeded fruits by swallowing them whole. I was lucky enough to see this one gag up a fruit pit from its voluminous gape. You could definitely get a small avocado in that mouth; the thing is almost the size of a crow. How I wanted to scurry after the pit and put it in my pocket, but I probably couldn't have found it if I tried, after it dropped 100 feet into the leaf litter. I'm sorry to say this is my best picture of a capuchinbird, but I'm not apologizing. The conditions were ridiculous. This is the kind of thing for which the BBC camera crew takes a month to construct proper scaffolding before the lekking season begins, then sits in blinds for ten hours a day to capture.

Capuchinbirds eat large-seeded fruits by swallowing them whole. I was lucky enough to see this one gag up a fruit pit from its voluminous gape. You could definitely get a small avocado in that mouth; the thing is almost the size of a crow. How I wanted to scurry after the pit and put it in my pocket, but I probably couldn't have found it if I tried, after it dropped 100 feet into the leaf litter. I'm sorry to say this is my best picture of a capuchinbird, but I'm not apologizing. The conditions were ridiculous. This is the kind of thing for which the BBC camera crew takes a month to construct proper scaffolding before the lekking season begins, then sits in blinds for ten hours a day to capture.Kevin Loughlin was kind enough to loan me this acceptable shot of his, which shows the capuchinbird in full Mas Macho glory. bbbbbbbrrrrrr waaaaaaahhhhhhh! Buenos huevos!

photo by Kevin Loughlin. He's taking trips to Guyana, people.

photo by Kevin Loughlin. He's taking trips to Guyana, people.As if seeing this well-balled bird of myth and legend were not enough, I had another bit o' fun in store. Weedon and I had a habit of hanging back behind the group, because we found lots of nice birds that way, being very quiet, or because we were being very silly, and interfering with everyone else. At any rate, we got separated, and I noticed that the trail sort withered away, then split off into threes, something that bothered me. If I took the wrong fork, then what? The Bushmaster Trail on Iwokrama Reserve is not a place I fancied being lost for long.

My mind flitted to Asaph, who had always been so careful to keep an eye on me as I investigated, meandered and snorfled my way through the forest. He was nowhere in sight. That was out of the ordinary. I stopped to gather my thoughts. Weeds was already starting to wig a little.

From behind a huge buttress root came the unmistakable cough of a jaguar. I'd never heard it, but I knew what it was. Oh, crrrrap.

And there was Asaph, also known as Jaguar, loving his little Wapushani joke (he had a million of 'em!), and about to get a brisk spanking from a very jittery Science Chimp.

And there was Asaph, also known as Jaguar, loving his little Wapushani joke (he had a million of 'em!), and about to get a brisk spanking from a very jittery Science Chimp.Labels: Asaph Wilson, bushmaster, calfbird, capuchinbird, Guyana birding, Iwokrama Reserve