Fuertes and Other Luminaries

As promised, we'll walk down the halls at the Lab of Ornithology, savoring the paintings that hang on its walls.

Here’s one that’s the rarest of the rare: A Fuertes study of the extinct Cuban macaw.

Of all the extinct birds in the world, the Cuban macaw is one that gives me great remorse. Imagine: A small macaw, perhaps the size of my chestnut-fronted macaw Charlie, but colored like a huge scarlet macaw. Wow, wow, wow. Looking at this painting, I could see that Fuertes painted it from a study skin. This colorful little macaw was extinct in the wild by 1864, and gone from the face of the earth by 1885.

Of all the extinct birds in the world, the Cuban macaw is one that gives me great remorse. Imagine: A small macaw, perhaps the size of my chestnut-fronted macaw Charlie, but colored like a huge scarlet macaw. Wow, wow, wow. Looking at this painting, I could see that Fuertes painted it from a study skin. This colorful little macaw was extinct in the wild by 1864, and gone from the face of the earth by 1885. From the Smithsonian Institution's web site, here is a picture of ornithologist Katie Faust holding a mounted Cuban macaw. People always smile for photos, but I'd bet she's sad, too.

From the Smithsonian Institution's web site, here is a picture of ornithologist Katie Faust holding a mounted Cuban macaw. People always smile for photos, but I'd bet she's sad, too. What a massive bill this bird had for its size. One wonders what hard nut it had to crack. It was unique in so many ways, such a loss to the planet. But Cuban macaws were edible, and they probably ate fruit that people wanted for themselves, and for that, they were extirpated, and another heaven and another earth must pass before such a one will be seen again.

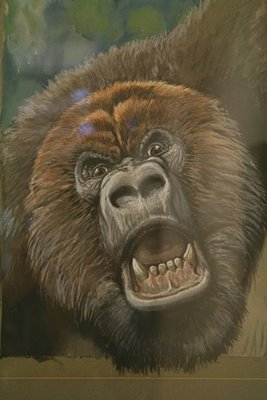

What a massive bill this bird had for its size. One wonders what hard nut it had to crack. It was unique in so many ways, such a loss to the planet. But Cuban macaws were edible, and they probably ate fruit that people wanted for themselves, and for that, they were extirpated, and another heaven and another earth must pass before such a one will be seen again.Just down the hall was a stunning gouache of a gorilla, a frequent subject for Fuertes. I’m always impressed by his handling of hair. Take it from me, when you’ve been painting feathers all your life, hair is kind of a stretch. This guy jumps right out of the frame at you. His hair is perfect. Gonna order up a plate of beef chow mein. I have GOT to do some portraits of Chet Baker in his young prime. Just have to. If LAF can master a gorilla, I can paint a shiny little dog.

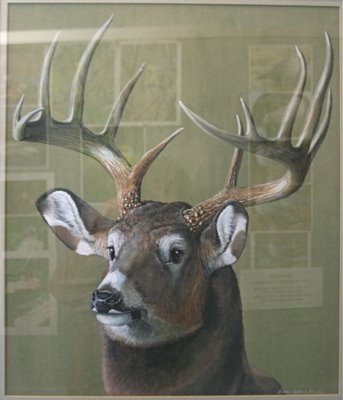

I adored this gorgeously drawn study of a whitetail buck—another unexpected treasure from Louis. My guess would be that he worked from a mounted head; a photo of him working in his studio shows several on the wall above his easel.

The sweep and structure of the antlers is so convincing and three-dimensional; the treatment of the deer’s various textures utterly convincing. What a wonderful subject for “life” drawing the ubiquitous mounted deer head would be. We all ought to try it. Those things are everywhere. Well, they're everywhere where I come from.

The sweep and structure of the antlers is so convincing and three-dimensional; the treatment of the deer’s various textures utterly convincing. What a wonderful subject for “life” drawing the ubiquitous mounted deer head would be. We all ought to try it. Those things are everywhere. Well, they're everywhere where I come from.There are other bird artists represented here, as well. Robert Mengel is one of my favorites—he was a painting ornithologist whose works are possessed of great accuracy, vigor and life. Here’s a running bobwhite by Bob, who passed away in 1990, another painter I would very much have loved to meet.

It’s really hard to paint something as intricately marked as a quail without getting too fussy. This is a masterpiece of understatement and grace. It has the mark of Fuertes, and Sutton, with whom Bob studied informally, but it is all his own, and instantly recognizable by its almost careless painterly beauty and truth to the species.

It’s really hard to paint something as intricately marked as a quail without getting too fussy. This is a masterpiece of understatement and grace. It has the mark of Fuertes, and Sutton, with whom Bob studied informally, but it is all his own, and instantly recognizable by its almost careless painterly beauty and truth to the species.Peter Scott was a British artist who simplified even further, and in my opinion has never been surpassed in his mastery of waterfowl in flight—even (or especially) by the legions of hook-and-bullet painters to follow. How many paintings of waterfowl flocks have been churned out--but are any of them as true or beautiful as this? Look how each swan in this flock has a slightly different angle and wing position; there are no cookie-cutter birds in Scott’s paintings.

Flocks are among the hardest thing a bird artist can attempt to paint, because the slightest variation in size or proportion can make the viewer think there’s a different species tucked in there. In addition, perspective demands that distant birds be depicted smaller—but making a convincing statement without suggesting that some of the flock members are miniaturized, or of another species, is extremely difficult. You can see me, hunkered over with my camera, reflected in the glass, wondering at the perfection of this small, seemingly simple but utterly exquisite painting.

Flocks are among the hardest thing a bird artist can attempt to paint, because the slightest variation in size or proportion can make the viewer think there’s a different species tucked in there. In addition, perspective demands that distant birds be depicted smaller—but making a convincing statement without suggesting that some of the flock members are miniaturized, or of another species, is extremely difficult. You can see me, hunkered over with my camera, reflected in the glass, wondering at the perfection of this small, seemingly simple but utterly exquisite painting.This has got to be one of the coolest Francis Lee Jacques paintings I’ve seen. Anyone who’s been to the AMNH in New York has seen Jacques’ work in the dioramas. A peerless painter of landscape and wildlife, Jacques could put birds and animals in space better than anyone before or since.

I love how he dwarfed the barn, giving us a (doubtless frightened) frog’s-eye-view of sandhill cranes. Jacques vastly preferred painting waterfowl and waders to songbirds. A paraphrased quote from him that I love: “The difference between warblers and no warblers in the landscape is very slight.” That little gift, from my friend, painter Bob Clem.

I love how he dwarfed the barn, giving us a (doubtless frightened) frog’s-eye-view of sandhill cranes. Jacques vastly preferred painting waterfowl and waders to songbirds. A paraphrased quote from him that I love: “The difference between warblers and no warblers in the landscape is very slight.” That little gift, from my friend, painter Bob Clem.An incubating female common nighthawk, painted from life by George Miksch Sutton. Sigh. Again, Sutton’s handling of the intricacies of the nighthawk’s vermiculated plumage—something an artist could fall into and not get out of—is masterful. To me, this bird fairly breathes; she is aware of being watched but holds tightly to her job.

I'm grateful to Charles Eldermire, Benjamin Clock, and Alan Poole, who took me to hidden areas of the Lab where many of these paintings hang. It was a privileged peek at a treasure trove of ornithological art.

Labels: bird painting, Francis Lee Jacques, George Sutton, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, Peter Scott, Robert Mengele

<< Home