The Fortunate Tooth

When I was eight years old, an extra tooth pushed through the roof of my mouth. My mother had had the same thing happen as a child. I doubt the extraction of my extra tooth by oral surgery was much nicer than hers in the 1920’s. To soothe the pain, Ida took me to an old bookstore in downtown Richmond near the dental hospital, the only time I can remember having anything bought for me in such a place. If I remember correctly, my dad met her at the bookstore and helped pick out just the right book for me. I remember picking up a weighty forest-green hardcover book from a table in the center of the dark, wood-paneled reading room, and knowing that this would be the finest book any child could have. It was A Natural History of the Birds of Eastern and Central North America, by Edward Howe Forbush and John Bichard May. I know now that the slightly florid but vivid writing style of Forbush and May, the expert integration of natural history information in readable anecdote and liberal quotes from direct observers, had a massive influence on my writing style. But though I read each species account many times over, it was the paintings I thirsted for most of all, and in particular the paintings of Louis Fuertes. I had never heard of him before; didn’t know whether he was alive or dead. I just knew that he got it right. His birds were alive.

In fact, Louis Fuertes died on August 22, 1927, his car struck by a train at a crossing. Ida, my mom, would have just turned 7 at the time. He’d been at dinner with friends; he’d brought his finest work, the bird portraits he’d painted in Abyssinia, along with him. They were flung free of the wreckage and miraculously unharmed; Louie was not so fortunate. I wonder where that crossing is, if anyone still knows. I’d like to go there, to see if any of that gentle man’s spirit still hangs in the air. I know I would have adored this man. I know it from reading his writings (To a Young Bird Artist by George Miksch Sutton is the perfect place to start). I know that just looking at his paintings.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology is a mecca for bird artists, with its vast collection of original Louis Fuertes paintings, as well as those of other luminaries. If you’ve hours to spend looking, Cornell has many of them up on the Web. What a gift, what a service to artists everywhere! Thank you, Lab! (and thank you, reader Harlow Bielefeldt, for alerting me to it).

Click here: The Fuertes Gallery at Cornell

If you don’t mind lousy pictures taken through glass in dim hallways, I’ll show you some of the paintings I was free to look at while prowling the innards of the Lab on my recent visit.

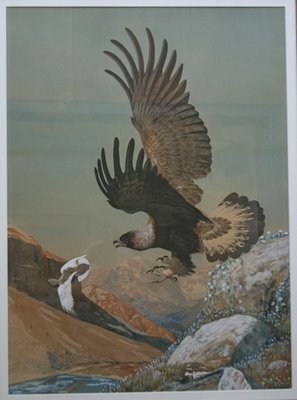

A golden eagle dives on a ptarmigan. Remember, in looking at these, that Louis had very little access to photographs of birds in flight. He likely worked from a mount here, though I don’t know that to be true. The birds’ wings are beautifully observed, even though the eagle’s somewhat static pose, with bill open, is a bit stylized and indicative of the fashion of the times. Modern photography of such action scenes would show the eagle’s feet flung far forward, directly under the head; the wings swept well back. I can only imagine the wonders Louis would have created had he had access to the kind of resources we take for granted.

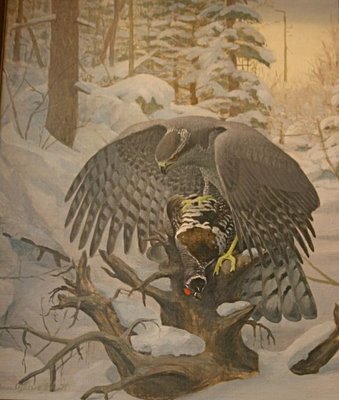

I love this oil of a goshawk mantling a spruce grouse; the intensity of the hawk’s pose, the rounded curve of its arching wings. The grouse is particularly lovely, and I imagine Fuertes observing captive hawks and falcons and sketching them in an effort to capture this pose. There’s a gorgeous dawn glow in the sky.

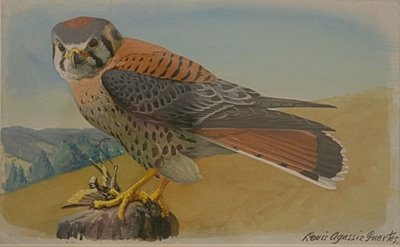

Fuertes did a series of paintings for Arm and Hammer Baking Soda, which included them on collectible cards found in each package. Man, as little baking soda as I use anymore, it’d take a lifetime to get a decent collection, but my dad remembers eagerly searching for each one when his mother got a new package. Seeing my delight with the Fuertes paintings in the book he and Mom gave me, he spent years looking for a set of them for me, writing letters to Arm and Hammer, asking if they might consider re-issuing them. My dad was a letter-writer, patient and persistent. So far, it hasn’t happened, but I did see a traveling exhibit of the paintings at the Boston Museum of Science in the 1980’s. This exquisite little kestrel was one of them.

He’s so perfectly captured the strange, boxy head and elfin look of the little falcon, I almost expect to see it rapidly bob its head as it peers at me.

He’s so perfectly captured the strange, boxy head and elfin look of the little falcon, I almost expect to see it rapidly bob its head as it peers at me.Walking through the Lab is such a treat for a bird painter; treasures abound. I think my favorite treatment was this one of a magnificent Fuertes mural, depicting a peregrine on the hunt over Fisher’s Island, New York. I spent some of the happiest days of my life bicycling Fisher’s Island as a field biologist for the Nature Conservancy. It is a little jewel, full of piney maritime forest, open grasslands, marshes and salt ponds and dunes, and all the birds that go with those habitats. This painting of a ring-necked pheasant's last flight perfectly evokes the sweep and scale of the island, the sparkling summer salt air, and the tantalizing knowledge that in a few hours, you can pedal its length and breadth, and see what there is to see.

I think that Louis would have glowed with pride to see the places of honor where his work now hangs, so beautifully integrated into a bustling ornithology lab.

I think that Louis would have glowed with pride to see the places of honor where his work now hangs, so beautifully integrated into a bustling ornithology lab.More Cornell treasures await.

Labels: bird painting, Fisher's Island, Forbush and May, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, my extra tooth, peregrine falcon

<< Home