Everything but the Bird

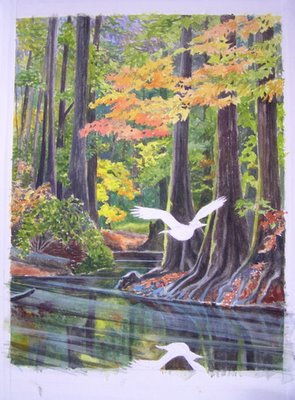

Because my day was mundane beneath describing, we have another installment of Building a Bayou. In the last progress picture, the water had gone in, and I'd painted a neutral wash over it to gray it down and make it recede a bit. A lot of what's going on in the current series is furthering the illusion of water. Light passing across dust and scum on the water's surface will help define its plane. Ever since my painter friend Mike DiGiorgio turned me on to it, Chinese white is my best friend. With it, I can create semi-transparent white washes that are really useful in painting things like bayou scum or the top of a bird's feathery back, washed in light.

Because my day was mundane beneath describing, we have another installment of Building a Bayou. In the last progress picture, the water had gone in, and I'd painted a neutral wash over it to gray it down and make it recede a bit. A lot of what's going on in the current series is furthering the illusion of water. Light passing across dust and scum on the water's surface will help define its plane. Ever since my painter friend Mike DiGiorgio turned me on to it, Chinese white is my best friend. With it, I can create semi-transparent white washes that are really useful in painting things like bayou scum or the top of a bird's feathery back, washed in light. You can see a magical disappearing snag on the lower left corner of the painting. I put it in, and my friend, painter Jim Coe, objected, and I agreed with him. (I'm sending jpegs around to my artist friends, soliciting comments. It's a new experience for me, but lots of fun). So I flooded the area with clear water from a loaded brush, let it sit a moment, and then lifted the water and the offending, finger-like snag right off the paper. See, watercolor isn't quite as unforgiving as people would have you believe when they tell you it's so "hard!"

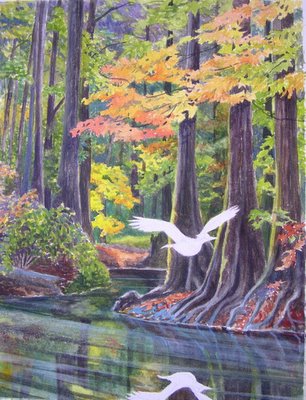

You can see a magical disappearing snag on the lower left corner of the painting. I put it in, and my friend, painter Jim Coe, objected, and I agreed with him. (I'm sending jpegs around to my artist friends, soliciting comments. It's a new experience for me, but lots of fun). So I flooded the area with clear water from a loaded brush, let it sit a moment, and then lifted the water and the offending, finger-like snag right off the paper. See, watercolor isn't quite as unforgiving as people would have you believe when they tell you it's so "hard!"Oh, yes...the Bird! I don't normally "allow" myself to paint the bird until I have wrestled its habitat to the ground. As you've seen, there was a whole lot of wrasslin' going on in this painting, a tall order, lots of trees and leaves and shadows and water and scum. It was all to set the stage for the star, to make her white wing patches shine against the gloom. She's really small, not even two inches long in the original, and getting the expression on her face just right is a challenge at that scale. It would have been easy, by comparison, to do what my friend painter Bob Clem calls a "Big Fat Bird Painting," where the star is front and center and big and fat with minimal context or habitat. Putting the bird believably in a habitat that the viewer can breathe in is much more demanding.

Mike suggests that I run some yellow leaves behind her primaries--and boom! she pops out of the picture, as she should.

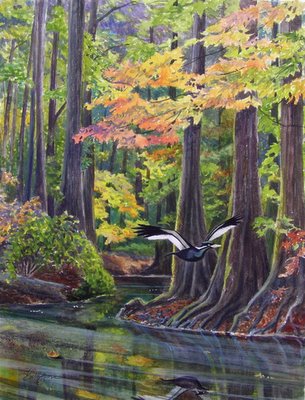

Why a female? Well, almost all the paintings out there are of males (nobody seems to be able to resist that dash of red), and I wanted to strike a blow for the girls. They've got a little more reproductive significance in a dwindling population, too. And the habitat's so colorful, a red crest would be almost lost in it. Last, seeing a female ivory-billed woodpecker is just that much more diagnostic, since female pileateds have plenty of red in their crests. So in she goes, and her reflection too, and I mess around making the reflection duller and duller, so you have to look for it.

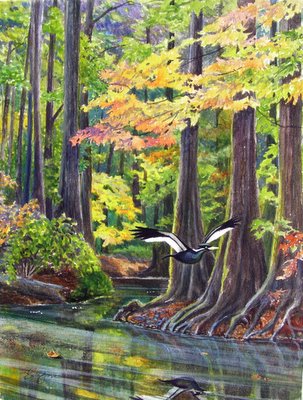

Why a female? Well, almost all the paintings out there are of males (nobody seems to be able to resist that dash of red), and I wanted to strike a blow for the girls. They've got a little more reproductive significance in a dwindling population, too. And the habitat's so colorful, a red crest would be almost lost in it. Last, seeing a female ivory-billed woodpecker is just that much more diagnostic, since female pileateds have plenty of red in their crests. So in she goes, and her reflection too, and I mess around making the reflection duller and duller, so you have to look for it.What I'm after is painting the experience of seeing an ivory-billed woodpecker, not just painting an image of the bird. I don't want it to look like anything--painting or photograph--that's out there. I want it to be completely unique.

There are some fun little devices that you can use when establishing the plane of water. Sparkles are scratched out of the paper with a razor blade. You're scratching the paint off, down to the white paper, and they can bring water to life. But you don't want to go overboard. My sister Micky suggested a floating red leaf. Good idea! Did that.

It's almost done. Debby Kaspari suggests that I differentiate the green bush on the left from the mossy bank--oh, good thought. So I darken the bank and lighten the bush, and there's now definition where there was none. The roots in the foreground are judged a little problematic by Will Reimann, so I vary their treatment and insertion into the water, paying attention to how each one goes into the water. Agggh, there's so much to pay attention to, but I slog on in my chest waders, wanting to turn this bird loose.

It's almost done. Debby Kaspari suggests that I differentiate the green bush on the left from the mossy bank--oh, good thought. So I darken the bank and lighten the bush, and there's now definition where there was none. The roots in the foreground are judged a little problematic by Will Reimann, so I vary their treatment and insertion into the water, paying attention to how each one goes into the water. Agggh, there's so much to pay attention to, but I slog on in my chest waders, wanting to turn this bird loose. Whether she's done or not, I'm finished with the painting, and I box it up and send it off to Arkansas, to decorate The Auk, and herald Jerry Jackson's important and thoughtful roundup of ivory-billed woodpecker events to date. Thank you, Jerry, for asking, and thanks to the editors and staff of The Auk for doing it proud in their reproduction.

Whether she's done or not, I'm finished with the painting, and I box it up and send it off to Arkansas, to decorate The Auk, and herald Jerry Jackson's important and thoughtful roundup of ivory-billed woodpecker events to date. Thank you, Jerry, for asking, and thanks to the editors and staff of The Auk for doing it proud in their reproduction.

<< Home